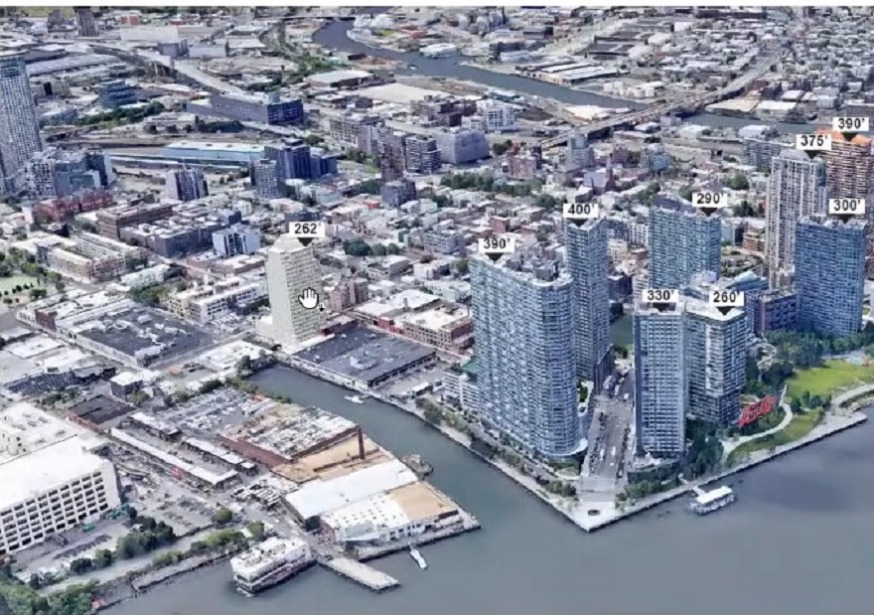

Rendering of the 23-story building. The building is located on the lefthand side tucked behind a revamped Paragon Paint building. (Screenshot of presentation displayed during the May public hearing)

June 8, 2022 By Christian Murray

A development company’s plan to build a 23-story residential tower on Vernon Boulevard was rejected by Community Board 2 last week.

Quadrum Global, an international investment firm, is seeking a zoning variance through the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA) in order to develop a tower at 45-40 Vernon Blvd., the site that is currently home to the dilapidated Paragon Paint Building.

The plan would involve rehabilitating the Paragon Paint building and developing a 23-story tower behind it.

The board voted to reject the zoning variance saying that the development would be out of character with the area. The variance, however, is not dependent on the approval of the community board, with its vote being advisory.

The community board vote took place over Zoom Thursday during its regular monthly meeting—but the video has yet to be uploaded to YouTube nearly a week later. Sources say that the meeting was Zoom bombed with porn—and attribute the delay to that.

Quadrum’s application for a variance will not have to go through the standard rezoning process known as ULURP since it is seeking the approval of the BSA. Therefore, its application will not be reviewed by the borough president and City Planning Commission—nor will it go before the City Council for a vote.

The application will go straight from the community board to the BSA, where the BSA will render a decision.

The BSA has a long history of approving zoning variances even when they have been rejected by a community board. For instance, the BSA gave the all clear to a developer to construct a 17-story hotel building at 32-45 Queens Blvd. several years ago, defying the wishes of Community Board 2 and then Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer at the time.

The Paragon Paint building at 45-40 Vernon Blvd. A developer seeks a zoning variance in order to develop a 23-story residential tower on the site (GMaps)

The Development Plan and Current Zoning

The variance, should the BSA ultimately approve the plan, would permit the developer to construct a 226-unit building with ground floor retail space.

The 23-story project would also include public access space that would go from Vernon Boulevard through to Anable Basin. Approximately 20 percent of the site would be dedicated for open space.

The site is zoned for manufacturing and Quadrum needs the variance to permit residential use. The site also needs a zoning change to permit a 262-foot-tall tower– which is well above the maximum height limit of 150 feet. The proposed development also doesn’t comply at present with some set back provisions, and the building envelope is larger than what current zoning permits.

An application for a variance was originally filed with the Building Standards & Appeals in 2015 but was put on hold. The plan was shelved since the site was included as part of the now-scuttled YourLIC proposal, an unsuccessful plan put forward by a number of developers that aimed to rezone 28 acres around Anable Basin.

The Paragon Paint development site is marked in red (Screenshot of presentation)

There are only two ways that developers, such as Quadrum, can get a site rezoned—either through the BSA or via City Planning’s traditional ULURP process.

The BSA track, which is a less cumbersome process, can only be taken if special criteria are met. Most developers, however, don’t meet the special criteria so they undergo the seven-month ULURP process.

To meet the BSA criteria, developers must prove that their property has a unique physical condition that poses a financial hardship—and hence the need for a variance.

Quadrum is claiming that the cost of cleaning up the industrial site has caused an economic hardship. The company says that it has spent $13 million remediating the property, which has involved clearing the contaminated soil, treating the ground water, as well as replacing the timber bulkhead/seawall that touches Anable Basin.

The developer argues that it needs a variance to offset the cost of the environmental cleanup. The company says that it was costly since the site was home to a paint factory where millions of gallons of paint and varnish were processed each year, with industrial materials leaking all over the site and into the river.

The BSA also stipulates that it will not approve an application for a variance if the proposal changes the character of a neighborhood.

The developer argues that the project is not out of character with the neighborhood, saying that it is in context with nearby waterfront developments. Furthermore, the developer’s representatives note that the tower is set back 80 feet from Vernon Boulevard and therefore claim it is not out of character with the smaller buildings on Vernon Boulevard.

The proposed tower would be 262 feet tall. The rendering shows how tall it would be relative to the towers by the East River (screenshot)

The BSA also stipulates that the financial hardship must not have been created by the owner or a predecessor in title.

Council Member Julie Won issued a statement to the Queens Post Wednesday criticizing Quadrum for not going through the standard ULURP process– and for electing to seek a variance from the BSA.

Council Member Julie Won (twitter)

“Any large zoning changes to the Paragon Paint building should go through the typical ULURP process, not through a BSA application, which is designed for projects of a much smaller and less impactful scale than this new residential tower,” Won said.

“Attempting to create large scale changes without input from the community, a full Environmental Impact Statement, Racial Impact Study and negotiations for deep affordability is wrong and should not be approved.”

“Developers must not treat the community as an obstacle to development and try to bypass them at every turn,” Won said. “We need real engagement at the onset of projects like this to create developments that truly benefit our city.”

Board Questions Whether Special Criteria Have Been Met

The board challenged Quadrum, questioning whether there is a true hardship, with members also saying that the project would alter the character of the neighborhood.

Several board members have said that Quadrum knew when it bought the site that it was contaminated so the hardship was self-imposed.

“You got into it with your eyes wide open,” said Kenneth Greenberg, a board member at a hearing last month, noting that the Quadrum is a sophisticated developer.

Board members at the May hearing also said that the $13 million hardship was a minor cost—in comparison to the profits that would be gained as a result of the variance. Furthermore, they noted that more than a quarter of the $13 million remediation costs would be subsidized through tax credits provided by the New York State Brownfield Cleanup Program.

Lisa Deller, co-chair of CB2’s Land Use and Housing Committee, said at the public hearing that the development would offer little for the community.

She said last month that the community appreciated that the site had been cleaned up—and that there would be public access from Vernon Boulevard to the Anable Basin—but argued that the community would be getting little else.

Deller also claimed that the developer did not meet the special criteria set by the BSA.

She said that the project is out of character to the immediate area which she said is low rise housing and light manufacturing. She insisted that the plan would alter the essential character of the area.

“The community is not getting much other than more gentrification and more density and more stormwater,” Deller said in May.

Christine Hunter, also a co-chair of the Land Use and Housing Committee, agreed with Deller last month.

“Light industry and arts—that is what this neighborhood is known for,” she said. “I don’t think it [the development] is appropriate.”

The plan, however, does have the support of local business groups such as the Long Island City Partnership and the Queens Chamber of Commerce.

Charles Yu, senior director of business assistance with the LIC Partnership, told the board last month that the project would bring much needed open space and provide access to the waterfront.

Meanwhile, Brendan Leavy, the business development manager with the Queens Chamber, advocated for the plan and complimented the developer for ensuring that the lower-density component of the project was closer to Vernon Boulevard, with the tower by the water.

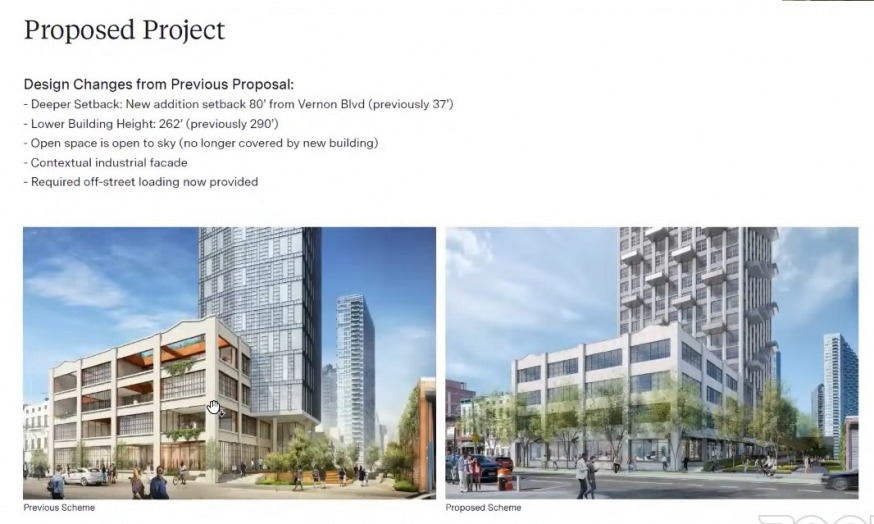

He noted that the development is smaller compared to the original 2015 BSA application. The tower in the original plan was slated to be 290 feet tall and set back 37 feet from Vernon boulevard.

The changes made from the original plan (Screenshot of presentation)

However, many local residents have told the Community Board that they oppose it.

Lisa Goren, a Long Island City resident who spoke last month, urged the community board to reject the proposal. “It alters the essential character of the neighborhood,” she said.

Diane Hendry, a long-time resident, also said that it was out of character. “It is widely out of context,” she said, saying that it would go up next to one- and two-story buildings.

She said the cost of remediation is also miniscule in relation to the overall cost of the project and revenue that would be generated.

“These costs are a tiny fraction of the profit that will be made if this is approved,” Hendry said.

She urged the community board to reject it and to send a representative with legal expertise to the BSA to refute the developer’s arguments.

site plan (screenshot)